Introduction

In this article, we'll explore the structure and basic flow of the _printf() implementation project, along with its essential components and their interactions.

Congratulations on embarking on this exciting project of building a custom printf function in C. I'm here to guide you through this journey, As one of the Learning Ambassadors for your cohort, ensuring you ace it and learn from the experience. Let's get started!

Project Objective:

The primary objective of this project is to develop a custom _printf() function that emulates the functionality of the standard library function printf(). As most people are aware, printf() is responsible for formatting and displaying output to the console in a versatile and adaptable manner. Let's examine the function prototype of this utility to gain a better understanding of its structure and purpose.

int _printf(const char *format, ...)

First is the return type, int

The function will have an integer return value int, which is the length or number of characters printed out excluding the null '\0' terminating byte used to end output to a string. This means that you have to keep track of the length of any string or number of characters you will format and print to the console(stdout (your terminal, etc)). NOTE: We are only keeping track of the length or number of things printed out to the console after being formatted. Next is the function name _printf which is simply the name of the function that this prototype describes—the name of what we are implementing or referring to.

The first parameter:

The first parameter const char *format also called the "format string" (I will be referring to it as such going forward), this format string is pointer to a constant string. explaining further; format holds or points to an address where an array of characters (string) is stored. This means that format is a pointer variable that points to a string of characters, and the characters in this string are constant. In other words, you cannot modify the characters through this pointer.

There are three logical ways in which you should treat or handle this string:

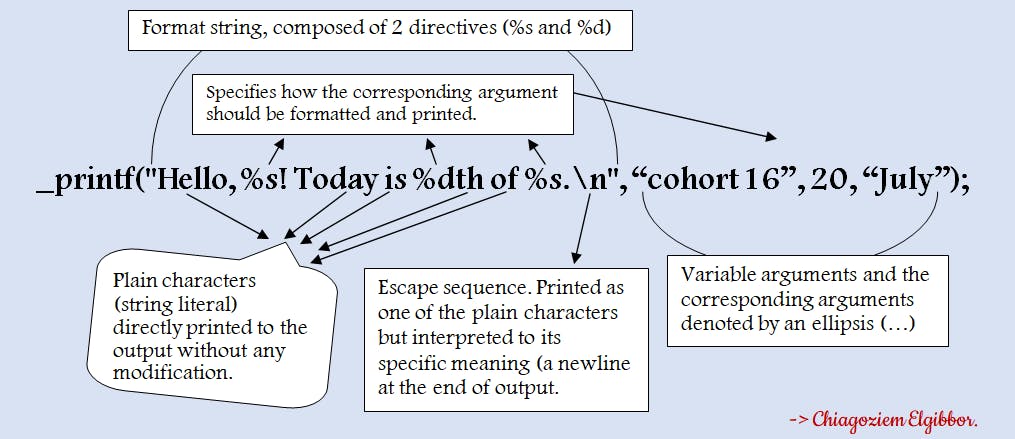

Plain characters: These are normal letters, numbers, or symbols that make up a string literal. They are directly printed to the output without any modification. For example, if the

formatstring contains an array of characters (string)"A","Hello, cohort 16"or"I am number 10", they will simply be printed as"A","Hello, cohort 16"or"I am number 10"to the standard output.Character escape sequence: These are combinations of characters that have a specific meaning. When they are encountered in the format string (the plain characters I discussed above), they are converted and displayed accordingly. For instance, escape sequences like

'\n','\t'; the first represents a newline character, which causes a line break in the output, and the next represents a Horizontal Tab, which inserts some whitespace or tab space to the left of the cursor and moves the cursor accordingly. You shouldn't worry about these characters because they will be handled and interpreted into their meaning when encountered in the plain characters segment I explained before.Format specifications: This segment involves or cannot be successfully implemented without the last parameter in the function prototype. The last parameter is three dots

...called ellipsis which makes our_printf()function a variadic function. Later in this article, I will discuss how we can implement and handle the variadic nature of this function. Back to this segment, Format specifications: They are special placeholders in the format string (const char *format) that indicate the specific format in which the next argument should be printed. Format specifications start with%followed by a conversion specifier (c,s,d, etc.). They indicate how the corresponding arguments should be formatted and printed. This brings me to the description offormatin the printf man page, which says "formatis a character string. The format string is composed of zero or more directives". So, what does this entail? means that the format string can contain zero or more directives. A directive is a special placeholder in the format string that specifies how a particular argument should be formatted and printed. In the context of this function, a directive is indicated by a%character followed by a conversion or format specifier (c,s,d,i, etc). For example, in the format string"Hello, %s! Today is %dth of %s.", there are two directives:(a).

%s: This conversion specifier specifies that the corresponding argument should be treated as a null-terminated string and printed.(b).

%d: This conversion specifier specifies that the corresponding argument should be treated as a signed decimal integer and printed. You might be wondering where these corresponding arguments are. They are the arguments represented or denoted by the ellipsis in the last parameter of the function. Let's talk about that now!

The last parameter:

The ellipsis (...): In C, an ellipsis (...) is used to represent a variadic function parameter which allows a function to accept a variable number of arguments of different types. "variable" here is just an English word, not the variables you declare while coding, and what this means in this context is that our _printf function is expecting or can accept any number of additional arguments after the fixed parameters, and the fixed parameter in our case is the content of our format string const char *format. So while printing the arguments or contents of our fixed parameter, if our loop encounters any directive (%s, %c, %d, etc.), we replace it with the value in our variable arguments. for example _printf("Hello, %s! Today is %dth of %s.", "Cohort 16", 20, "July");. In this example, %s will be replaced with "cohort 16", %d with 20, and %s with "July". But how do we access, format, and make use of these variable arguments accordingly? That's what we will discuss next. Below is a pictorial representation I came up with that can help you understand this basic structure.

Consolidating everything we've discussed

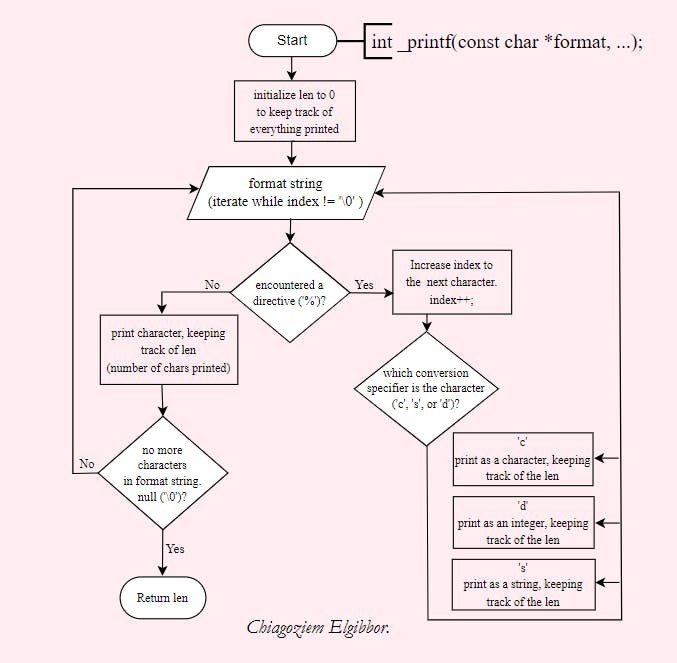

While I'm making sure you understand the flow and structure of this project and its implementation, I also don't want to leave you with a verbatim solution to anything related to it. Coming up with your own logic and approach to solving this ensures you meet the learning objectives.

With that being said, I will provide a flow chart and brief explanation, or pseudocode, that can give you a smooth headstart.

Working with the variadic arguments

With reference to the structure of our curriculum and learning track in Alx, I am very certain that the concept of variadic functions has been treated, and I am also confident that you are familiar with it and their implementation. As such, I will refer to their uses in this explanation, making the assumption that you already have a good grasp of the concept.

In our implementation of the _printf function, we are dealing with a variadic function, which allows us to work with a variable number of arguments. However, it's essential to have at least one mandatory argument in the parameter list, and in our case, the format string serves as that mandatory argument. The format string must be the last argument before the ellipsis (...).

To access the variable arguments that correspond to the format directives (e.g., %s, %c), we make use of macros defined in the stdarg.h header. The va_list macro provides access to this list of variable arguments. By declaring a variable of type va_list, such as va_list arg_list, we can inherit or have access to this list of arguments. We initialize our variable arguments from the specified position (right after the format string) using the va_start macro (e.g., va_start(arg_list, format)).

Now, while iterating through the format string, when we encounter a directive (e.g., %s), For us to print the string argument that corresponds to this directive, we use the va_arg macro to access individual arguments in the list according to their data type, which is also specified in its parameter. For instance, when printing this string, we access the string characters individually as va_arg(arg_list, char *), where the second parameter char * specifies the data type of the argument we are trying to print, which is a string literal. We then assign this to a variable, and to print the entire string, we loop through that variable and print its individual characters.

for a visual understanding of what I just said, let's have a basic pseudocode for this below

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdarg.h>

int _printf(const char* format, ...)

{

int len = 0; /* Keep track of the number of characters printed */

va_list arg_list; /* Declare a list of all variable arguments */

va_start(arg_list, format); /* Initialize starting position */

/* Loop through the format string */

for (int i = 0; format[i] != '\0'; i++)

{

if (format[i] == '%')/* if a directive ('%') is encountered */

{

i++; /* Move to the next character after '%' */

if (format[i] == 's')//Check for the format specifier (e.g., %s)

{

char *str

str = va_arg(arg_list, char *);/*Access the str arguments*/

int j;

/* Loop through the string and print its characters */

for (j = 0; str[j] != '\0'; j++)

{

putchar(str[j]);

len++; /* Update len with the number of chars printed */

}

}

/*Implement other format specifiers for different data types -*/

/* (e.g., %c, %d) similarly. */

/* Update len accordingly for each specifier */

}

else

{

putchar(format[i]); /* Print regular characters */

len++; /* Update len for each character printed */

}

}

/* Clean up the list when you're done formatting and printing */

va_end(arg_list);

/* Return the total len of every character printed to the console */

return len;

}

This is just a basic demo to print the corresponding argument of %s. You can see that formatting this directive with its corresponding argument is a separate chunk of implementation on its own. By understanding how to access variable arguments corresponding to a string conversion specifier like %s, you can enhance the _printf function to handle multiple format specifiers effectively. Instead of handling the formatting for each specifier within the same function, you can create separate helper functions for each specifier (e.g., print_int, print_char, print_string, etc.). With this approach, whenever _printf encounters a format specifier, it then calls the corresponding helper function to format and print the argument accordingly. You should also consider the number of characters printed in that helper function, returning them afterwards, and updating the len variable of _printf with the returned value from the helper function. Now Each helper function will handle the specific formatting logic for its respective specifier, ensuring a clean and organized implementation.

Conclusion

The explanations I provided offer a basic understanding of the implementation flow for this project and how you can handle its variadic arguments. By following this guide, you can gain insight into the essential steps for accessing and processing variable arguments based on format specifiers.

It's important to note that this explanation only serves as a smooth starting point for your project, helping you comprehend some useful use cases of variadic functions, va_list, and va_arg macros. However, for a more optimized implementation, additional considerations are required. For a more refined and efficient implementation, concepts like switch-case statements or function pointers should be integrated. By employing switch-case statements, you can streamline the handling of different format specifiers, making the code more organized and easier to maintain. Additionally, function pointers allow for the dynamic selection and execution of specific formatting functions based on the encountered format specifiers.

Thank you for reading, and Good luck with your project!

You can keep an eye on the ask_learning_ambassadors channel and your official cohort channels too, where I will be announcing scheduled live-learning sessions to walk you through these concepts and their implementation and also offer necessary assistance.

Care to reach out or connect with me? Here you go! Twitter, LinkedIn, GitHub